Prior to the internet, this could easily be a multi-year endeavor of parsing through record stores, flea markets and garage sales. Traditionally, a music fan had to read a book or article, then go track down whatever recordings were discussed.

The obvious advantage of podcasting as a medium for telling music history is that you can listen to a given song as it’s being discussed. In Episode 3 of Season 2, Coe bluntly explains how the “sounds we associate with country music came from poor people working out techniques to produce art on cheap, low quality, often damaged, sometimes straight-up broken instruments.” Episode 7 of the first season covers Linda Martell, the first black woman to perform on the Grand Ole Opry, along with the racist label head who kick started her career. Episode 2 of Season 1 breaks down country radio’s sexist gatekeeping, for example. Hosted by Tyler Mahan Coe, the show examines forgotten or misunderstood country history while placing this history within the structural contexts of gender, race and class. One of the best examples comes from Cocaine and Rhinestones, a podcast about the history of twentieth century country music. The medium is both popular with the general public and tailor-made for sonic analysis. The recent essay collection The Honky Tonk on the Left brings together a diverse cast of professors to challenge the received wisdom that the genre is solely home to political conservatism.īeyond traditional academic channels, podcasting offers a new way of studying music history. Among other exciting work, Amanda Marie Martinez recently published on the intersection of punk and country in Reagan-era Southern California, and Francesca Royster has an innovative piece of the power of country artist Valerie June (and dropping new book in October 2022 called Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions!). Within the academic world, though, a new generation of scholars is bringing country history to the forefront, all while complicating the inaccurate racialized mythos perpetuated by the industry. A search of the nation’s university libraries reveals just four copies available in the entire United Sates. If you’re lucky enough to score a copy of Philip Self’s Guitar Pull: Conversations with Country Music’s Legendary Songwriters, for instance, the book will set you back over $70. These albums didn’t even make it to CD.īooks about country music history are even more rare, and some of the most insightful publications are long out of print. Just try to find Stoney Edwards’ 1971 classic Down Home in the Country or Patti Page’s 1951 collection Folk Song Favorites on the streaming platform of your choice. Many of country music’s best recordings will never make it to digital archives or streaming services, save for a few generous YouTubers who upload their personal record collections for public enjoyment.

If you’re a country music fan, you might be aware of the genre’s central contradiction: for all the references to classic, traditional, “real” country music, most of this music has not been preserved. Past posts have examined Gimlet Media’s Fiction Podcast Homecoming, Amanda Lund’s The Complete Woman? Podcast Series, and how podcasts position listeners as “stoic.” Today’s entry examines how country music podcasts do–or do not–consider the sound of the music itself in their episodes.

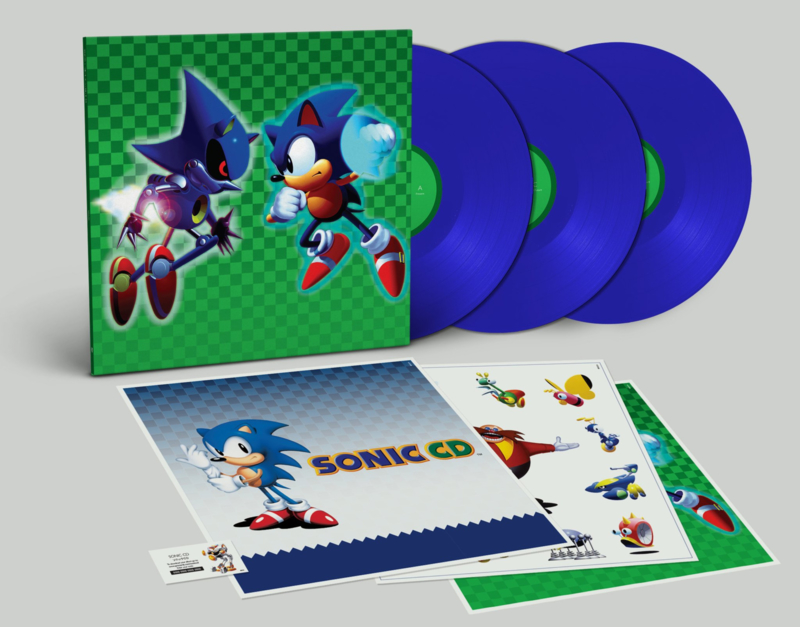

#Sonic cd soundtrack listen series

In advance of International Podcast Day on 30 September, Sounding Out! finishes a series of posts exploring different facets of the audio art of the podcast, which we have been putting i nto those earbuds since 2011.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)